The picture he creates is an autodidact’s fantasy of the life of the mind. A touch of Miss Jean Brodie without the fascism a touch of Mary Poppins without the magic. She assembles herself, or Neil assembles her, out of a series of tics and poses: she smokes, dresses with unostentatious style, speaks with confidence and wit about European history, philosophy and culture.

To his more radical classmate Geoff, she is a classic British dilettante, ‘not so much old-school as antique-school’. Who, then, is Elizabeth Finch? To Neil, she is a glamorous intellectual: ‘high-minded, self-sufficient, European’. After Elizabeth’s death, he sets himself the double task of completing her unfinished or abandoned work on Julian while trying to reach some understanding of who she was. Twice divorced, he is oblivious to the advances of one fellow student while embarking on a brief fling with another.

Neil’s Platonic infatuation with Elizabeth, to whom he becomes a kind of protégé, serves as a counterpoint to his distinctly unsatisfactory romantic relationships. An unsuccessful actor, sometime waiter and intellectual striver, Neil joins a venerable line of Barnesian protagonists, men just about intelligent enough to grasp how limited their knowledge of others must be, but never quite sharp enough to realise how little they understand themselves. In the middle, in the form of a biographical essay, comes Neil’s effort at piecing together Elizabeth’s scholarly notes on the much-maligned Emperor Julian. The framing narrative consists of Elizabeth’s life story – or, rather, the mostly unsuccessful attempts of her admiring student Neil to construct that story.

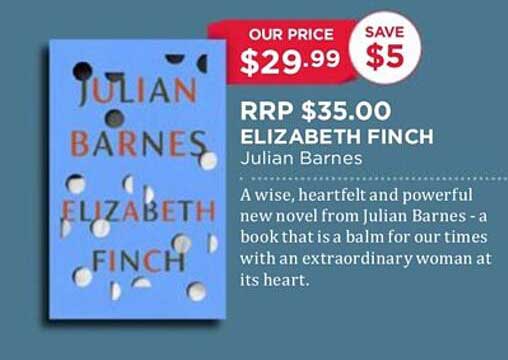

J ulian Barnes’s new novel has two main characters: Elizabeth Finch, quietly charismatic extramural tutor for mature students at the University of London, and Emperor Flavius Claudius Julianus, aka Julian the Apostate, the last non-Christian ruler of Rome.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)